My interest in the history of Africans in Russia was born from the interweaving of different events: first a first reading in high school evoking Pushkin and his ancestor Hanibal, then my knowledge of Russia, its language, its culture and of its history after six and a half years of university studies in Moscow.

I had to answer the following questions: how could the greatest Russian writer of all time have an African filiation in his genealogy? Who was this Hanibal who was said to be Ethiopian? Why in Russian texts was it called "arap" (negro) and not "efiop" (Ethiopian, Abyssinian)? How had he ended up in Russia?

This study on Pushkin's ancestor that I undertook from 1992 fascinated me. Because finally, I began to discover the true story of this man and the important historical role he played in Russia. I then said to myself that Africans and non-Russian speakers who would never have access to these Russian texts had to know the life and works of this African from the diaspora who had become a general and an eminent fortifier in Russia. in the 18th century.

This is how I decided to write my first book, which was published four years later in 1996 by Présence Africaine under the title Abraham Hanibal, Pouchkine's black ancestor. It was translated into Russian in June 1999 by Molodaya Guardia editions in the GZL (Life of famous men) collection. In the introduction to his book on South Africa published in Moscow in 1972, the eminent Russian Africanist Apollon Davidson regretted that African historical figures were very little known and that no African figured among the hundreds of biographies of famous men from around the world published in this prestigious collection. I am therefore proud that Hanibal is the first African historical figure to appear in the largest collection of biographies published in Russia “Life of Famous Men” published by Molodaya Guardia.

My research on Hanibal led me to present in the 1990s and early 2000s several papers at conferences in Benin, Russia, the United States, France including Guadeloupe and Guyana, Cameroon, and to publish a series of articles on the slave trade in the direction of Russia, on the real country of origin of Abraham Hanibal which is present-day Cameroon and not modern Ethiopia as it was generally accepted throughout the world, on the Pushkin's African heritage and on the African theme in his work in Russian, French and American journals including The Herald of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Le Messager de l'Académie des Sciences de Russie), Diogenes, Research in African Literatures, Sociétés africaines and Diaspora, or in the collective work of Unesco on the slave trade, The chain and the link, A vision of the slave trade.

I also took part in the 1990s in three documentary films made by Russian television channels on Hanibal and Pushkin. I was the main historical consultant for the film Sous le ciel de mon Afrique, directed by Konstantin Artioukhov, produced by the Pushkin National Museum of Russia in St Petersburg, part of the filming of which was carried out in France and Cameroon in February 2000.

The controversial question of General Abraham Petrovich Hanibal's African country of origin

Born in 1696 in Africa, Hanibal had been taken prisoner and sold as a slave around the age of seven (1703) in Constantinople, the capital of the Ottoman Empire. The question of the African country of his birth has given rise to the most serious controversies. Some scholars even considered it a riddle that would never be solved. Yet in all publications in Russia and abroad on Pushkin and his black grandfather, it was mentioned that the latter was from Ethiopia or Abyssinia.

In one of his autobiographical writings, Hanibal clearly mentioned in 1742 the name of his birthplace, but he did not specify the name of the country where this city was located:

"I am from Africa, of illustrious local nobility, I was born in the city of Lagone, on the lands of my father - who, in addition to this city, reigned over two other cities."

It is to this day the only document that has been found in which Hanibal evokes his African origins and gives valuable information about his place of birth. Speculations on the existence or not of this city are at the origin of multiple legends. But it should be clarified that these speculations did not take place during Hanibal's lifetime. For his contemporaries, he was quite simply an African Negro. His precise African origin was irrelevant. Also Hanibal could have been "a familyless negro bought in a Constantinople slave market" as Vekstern claimed.

Helbig, Hanibal's first biographer, considered that he "was a Negro, brought to Russia from Holland by Peter I as a ship's boy." When around 1786, his Prussian son-in-law, Rotkirkh, wrote in the "German Biography", a handwritten document of a few pages in German on Hanibal, that the latter was a "Negro from Abyssinia", his concern was to prove that his Negro father was a direct descendant of the famous Hannibal of Carthage. Rotkirh is thus the first to forge a legend around the origins of Hanibal:

“He was an African Negro, originally from Abyssinia; the son of one of the most powerful and influential princes in the region. He was proud of his direct ancestry with the line of Hannibal, the menace of Rome. His father was a vassal of the Ottoman emperor... Following the oppression and the penalties of which he was the object, he rebelled at the end of the last century, in the company of other Abyssinian princes, against the sultan, its ruler; small but bloody armed conflicts ensued; but in the end force prevailed, and the eight-year-old named Hannibal, the youngest of the reigning prince, was sent with other youths of noble family to Constantinople to serve as hostages..."

Vekstern, another Russian biographer of Hanibal, wrote in the late 19th century:

"The Negro Ibrahim who later became Abraham Pétrovitch Hannibal, contrary to the opinion of Pushkin who affirmed that he was the son of a reigning prince of North Africa, was in fact an ordinary negro without a family, image of the many others that were brought to Constantinople every year, to be sold in the market. When he was a child, he found himself a prisoner with the Turkish sultan, and from there he was taken to Russia with two other negrignons to the Court of Peter the Great in the early years of the century.

Vladimir Nabokov has shown that various passages of the "German Biography" had been of literary inspiration. Indeed, one of the most popular novels in Europe at that time had an Abyssinian prince as its hero. This is Rasselas, Prince of Abyssinia, by the English writer Samuel Johnson. Rotkirkh made Hanibal another prince of Abyssinia living in the splendor of his father's sumptuous palaces, whom half-brothers and their mothers, jealous of his favorite status, sent, following a plot, as a hostage at the Ottoman Court.

In 1899, the Russian journalist Dmitry Anoutchine claimed to have discovered the famous city of Lagone in Ethiopia. He first recalls Pushkin's thesis of Negro origin before refuting it:

“After the poet's death, his Negro origin (through Hannibal) was accepted by almost all biographers. Yazykov, Longuinov, Khmyrov, Barteniev, Annenkov - all call Abraham Petrovitch Hannibal, negro. In his very last work, "A. S. Pushkin in the Alexandrian era" (1874), Annenkov, using the German biography of Abraham Petrovitch Hannibal preserved in the documents of the poet, indicates that the Negro of Peter the Great was the descendant "of a family of Abyssinian princes", but he does not stop at this indication; pointing out that even Pushkin had not used it in his account of his ancestor, and assuming, obviously, that this indication could hide "a well-meaning lie" from the Hannibals, the ambition to elevate "the honor of the family". "The general character of the biography of the famous negro, - concludes Annenkov, - remains...even today tinged with legends and fables, and it is doubtful that we will ever obtain the entire historical truth."

Anoutchin decided to put in the foreground the indication of the "German Biography" on Abyssinia and he sought the homeland of Hanibal in the territory which was called Abyssinia in the 19th century and which does not correspond at all to the Abyssinia of the time when Hanibal was born. In the General History of Africa, published by UNESCO, it is specified about the term "Habesistan" or "Abyssinia" used in the Ottoman sources (16th-18th century) that it "encompasses all the territories from southern Egypt to the island of Zanzibar or Mozambique in East Africa”.

The author of the "German Biography", as well as most of his contemporaries who knew almost nothing about Africa, could think that Abyssinia was this immense empire which bordered "to the west with the kingdom of Kongo, the Niger River” and had as its natural border to the south “the Moon Mountains”. It would have been enough for Anoutchine to study the old maps of Africa to understand that Abyssinia or ancient Ethiopia designated almost all of Africa located south of Egypt. However, the academician preferred to limit his research to the territory of Ethiopia which was contemporary to him.

To fully understand Anoutchin's article, it is necessary to shed light on two key terms, namely, Arap, (Black, Negro, borrowing from the Turkic languages) in Old Russian and Abyssinian (Ethiopian, the oldest Russian word designating the Blacks, borrowed from Greek), different terms having been used in the Russian language to designate the black-skinned inhabitants of Africa. For Anoutchine, the difference between these two terms is fundamental: “The black race is intellectually and culturally inferior to the white race”. As for the Abyssinians, he considers that they are a different race, mixed with Semites and Blacks, therefore, "capable of creating a much more advanced culture". Like other European anthropologists of his time, Anoutchine places the Abyssinians in the famous race of "hamites" or "hamites", white peoples who would have civilized the African continent...

Anoutchine was persuaded "that it was permissible to doubt that a thoroughbred Negro...could show such talent as did Ibrahim Hannibal...and that, finally, the great-grandson of this Negro, A.S. Pushkin, marked with his person a new era in the literary and artistic development of a European nation”. It was humiliating for the academic anthropologist to accept Pushkin's idea of Negro origin. So, in spite of the fact that Hanibal considered himself an African Negro and his contemporaries also considered him as such, as well as Pushkin and the other descendants of Hanibal, in spite of all these testimonies, it is Anoutchin's opinion which has been recognized and authoritative for a century in Pushkin's Studies. It is true that Marina Tsvetaeva, (famous Russian poetess) wrote that “before racism was born, Pushkin, by his very birth, ruined it”. As for Vladimir Nabokov, he called Anoutchin's article “a composition that deserved nothing but criticism, from the historical, ethnographic and geographical points of view”.

Nabokov was absolutely right: many facts of a historical and geographical order speak against the "Hamito-Abyssinian" version. Anoutchine had among other things affirmed that he had located the region of Loggon in Abyssinia, in the province of Hamassien without adding a map of the said territory. He also assumed that Hanibal's father was the reigning prince of this region of which the city of Debaroa (Dobarva) was the capital. According to him, this city “could also be called Logone like the whole region” (emphasis added). N. Khokhlov, a contemporary researcher, visited the places described by Anoutchine without finding the slightest trace of Logone there. He only found a small village called Logo, a few kilometers from Debaroa. In addition, local historians and specialists in cartography assured him that apart from Logo, there was no other locality of the name close to Logone and that there had never been a city of this name. in their country. Similarly, the proper name Lagane is absent from local onomastics. Disappointed at not having found the slightest concordant clue in northern Ethiopia, Khokhlov attacked "Pushkin's imagination"! But isn't it more logical to consider that since in Abyssinia there was no town named Logone and the name Lagane was unknown there, we had to deduce that we hadn't looked for the right place?

Having concluded in the inconsistency of the Ethiopian thesis which was fabricated from scratch by the Russian scholar Anoutchine, I proceeded from 1992 to 1995 to new research which enabled me to locate the birthplace of Hanibal in the former Central Sudan. Indeed, Logone/Lagone (in Russian) which could not be found in Ethiopia, does exist in the Lake Chad basin and was the capital of the Kotoko Principality of Logone (now Sultanate of Logone) located today in northern Cameroon and Nigeria and southern Chad. Many geographical, historical and linguistic arguments support my thesis of a kotoko origin of Abraham Hanibal. As for the capital of this kotoko principality, Lagone or Lagone-Birni (the large fortified city), - where Hanibal was born at the end of the 17th century, it is nowadays in Cameroon. This led me to support in 1995 the thesis of the Cameroonian origin of the African great-grandfather of Alexandre Pouchkine:

After a systematic study of African history and toponymy from the 16th to the 18th centuries, I have come to the conclusion that there is only one city in Africa by the name of Logone and that it is not in “Abyssinia” but in the center of Africa, south of Lake Chad, in the extreme north of the modern state of Cameroon, in that part of Africa which was once called central Sudan. European travelers mentioned the city of Logone as early as the 16th century among the African capitals of the region. It is an old fortified city which was the capital of the principality of Logone. Wasn't it therefore knowingly that in his request to the Senate, Hanibal had named only his hometown without mentioning the name of the country? The principality over which his father reigned had the same name as the city where he was born!

The history of Logone from the end of the 17th century shows that the principality was often attacked by its powerful neighbors, in particular by the sultanate of Baguirmi, which maintained commercial relations with the Ottoman Empire. Ibrahim, who was the son of the Prince of Logone, could have been taken prisoner following one of these conflicts and taken to Constantinople. Logone was led at that time by the Miarré (princely title) Broua. The latter is known in the history of Logone as the builder of the capital, a city with massive fortifications which surprised more than one European traveler passing through the region until the 19th century. One can therefore wonder if the talents of fortifier shown by Hanibal in Russia had not been inherited...

A few more arguments. The Prince of Logone at the end of the 17th century had under his authority three important towns, which confirms Hanibal's statement in his petition to the Senate. In addition, the city of Logone is located on the banks of a long navigable river (one cannot help but think of Hanibal's story of his kidnapping on board a boat).

Another thing: the word "Lagané" designates the river in the local language. And the inhabitants of Logone are "Lagané or Lagouané". Thus, the only two words of the African mother tongue of Hanibal - which he himself retained and transmitted, namely, the names of his birthplace, Logone, and of his sister, Lagane -, exist in the language inhabitants of this principality! In view of all these facts, it seems to me that we can say with conviction that it is precisely the city of Logone in the Lake Chad region that Ibrahim Hanibal had designated as his homeland. In any case, I have not found any other city elsewhere in Africa, and then, the history of this African city of the XVIIth century corresponds completely to what we know of Hanibal's childhood.

My work sparked heated debate in Russia from 1995 to 1999. In the end, in Russian scientific circles, I received almost unanimous support. Several works published in Russia immediately after my work in the 1990s recognized that the thesis of an Ethiopian origin of Hanibal was unfounded and took up the results of my research:

- Collectif, dir. TCHELYCHEV E.P., de l'Académie des Sciences, Pouchkine et l'Orient, (Puškin i mir Vostoka) Moscou, Editions Nauka - Académie des Sciences de Russie, 1999, 431p.

- Oeuvres complètes d'Alexandre Pouchkine, Edition académique, Voskresienie, 1997, volume n°17

- Etudes Russes, vol.2, N°3 Saint-Pétersbourg, 1996

- Vladimir Nabokov, Commentaires du roman d'A. S. Pouchkine "Eugène Onéguine" (Vladimir Nabokov, Kommentarij k romanu A. S. Puškina "Evguenij Onegin"), Saint-Pétersbourg, "Iskusstvo-SPb", "Nabokovskij Fond", 1998, 928p.

- BESSONOVA A.M., Les Hanibal en Russie, (Gannibaly v Rossii), Saint-Pétersbourg, Editions de l'Université de Saint-Pétersbourg, 1999, 212p.

- GRANOVSKAÏA N.I., Ensemble avec Pouchkine (Vmeste s Puškinym), Saint-Pétersbourg, Editions Notabene, 1999, 217p..

- DROUJNIKOV Youri, Le prisonnier de la Russie (Uznik Rossii), Moscou, Izograf, 1997.

- Hundreds of publications in the Russian press have also presented my work to the Russian public over the past 28 years.

My works have received many echoes all over the world. More than a hundred radio and television programs in Russia, Africa, France, Great Britain, Belgium, Switzerland, the United States, and more than a hundred newspapers and magazines in the international and pan-African press ( Cameroon, Benin, Senegal, South Africa, Mali, Tunisia, Ivory Coast, etc), the New York Times, the Times Literary Supplement, Le Temps, Le Monde, L'Express, L'Histoire, La Quinzaine littéraire, Telerama, TF1, Jeune Afrique, Afrique Asie, Jeune Afrique Economie, Amina, Africa 24, Télésud, Vox Africa, Ubiznews, Africa International, Afrique Education, Radio Africa N°1, Continental magazine, Afrique Magazine, Amina, etc.

Finally, in the years 1999-2000, a two-hour course on my work relating to the North Cameroonian origin of Abraham Hanibal was included in the Pushkin study program of certain schools in the Moscow region, in Russia. In the United States, a symposium on the Africanity (Cameroon) of Pushkin was organized at Harvard in April 2008, of which I was one of the main speakers.

In addition, the Russian translation of my book obtained in September 1999 the Prize for the best foreign book on Pushkin and the Pushkin Prize of the Bicentenary awarded in 1999 by the Russian Foundation for Culture for my “significant contribution to the knowledge of the life of Pushkin”.

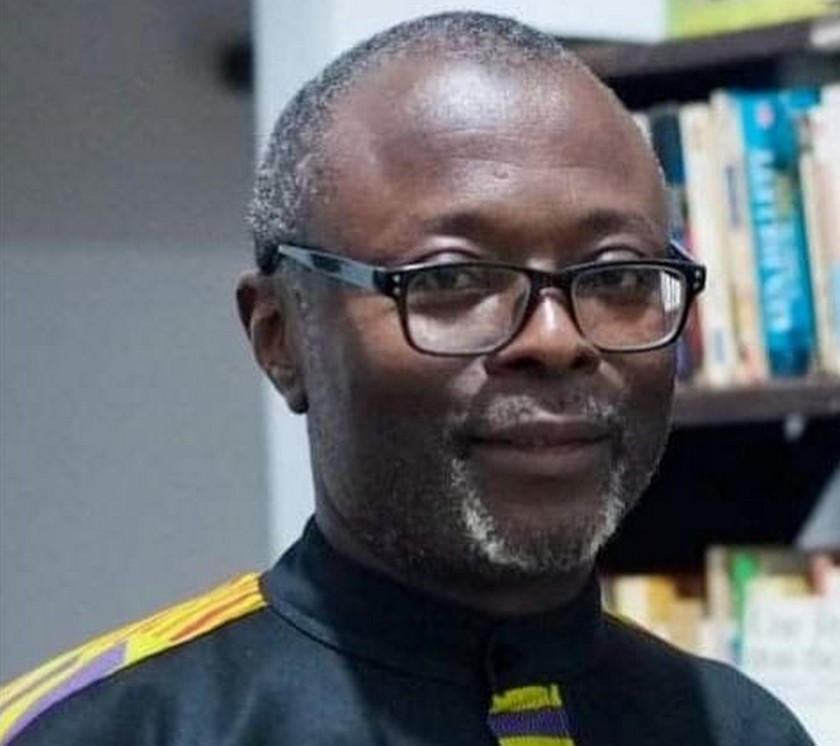

By Alcali Dieudonné Gnammankou,

historian, University of Abomey-Calavi, Benin.

*This article has been translated from French into English by Marcus Boni Teiga