The Empire of Mali or the Mandingo Empire was one of the most famous empires in Africa. Founded by Soundjata Keita, it is one of the great prides of Black Africa. He notably produced the famous Charter of Manden or Charter of Kouroukan Fouga.

The birth, decline and then the fall of the Empire of Ghana in the 12th century and other Empires which will succeed it - Sosso Kingdom (12th - 13th century), Empire of Mali or Mandingo Empire (10th - 15th century) and Songhai Empire (15th-16th century), marks a pivotal period in the socio-political and even ethnic recomposition in the Niger Loop (Boucle du Niger).

The Sosso Kingdom, founded by the Blacksmith Aristocracy and fiercely hostile to Islam, did not manage to resist for very long. The legendary Soundiata Keita got the better of his resistance against Soumaoro Kanté or Soumaworo Kanté during the famous battle of Kirinia in 1235.

The emergence of new powers, in particular powerful kingdoms, and the various interbreedings lead to a dispersion of the large Soninké sociolinguistic group across West Africa (Senegal, Niger, Guinea, Gambia) and reveal sub-groups among including the current Bozo and Songhai of Niger. "

The most important ethnic group – that of the Moors (the Biçān) – at the end of the 19th century was overwhelmingly Arabic-speaking. There are still a few thousand Berber speakers (especially in the western part of Trarza), but this is the last generation where there are still Berbers who do not speak the ḥassaniyya Arabic dialect. The installation in Western Sahara (mid-14th-17th century) of the Maquil-Hassane tribes and the warlike and political preeminence they conquered over the Berbers is at the origin of the adoption of the language of the victors (the ḥassaniyya) by the Berbers, defeated militarily. This rapid Arabization is however probably not unrelated to the fact that the Berbers (called Sanhadja in Arabic, by deformation of Zénaga) had been profoundly Islamized by the Almoravids, from the 11th century, and had already undergone an important cultural Arabization which made them the true representatives of the Arab language and culture, in the face of the Arab victors, who were much more uneducated and disbelieving1”.

Charles Monteil and Maurice Delafosse have already debated whether it was the Soninké that Arab chroniclers identified with Zenaga or Sanhadja. If the first was tempted to see it as a probability, the second was categorical to say that it was impossible to confuse the two. “Anyway, it was under the reign of these Sissé, whom Massoudi and the other Arab authors formally claim to have been Blacks, that the State of Ghâna reached its apogee. According to the testimony of Bekri, Yakout and Ibn-Khaldoun, its power was felt from the 9th century on the Zenaga or Sanhadja Berbers (Lemtouna, Goddala or Djeddala, Messoufa, Lemta, etc.) who had recently pushed their way forward. - southern guards as far as Hodh and in present-day Mauritania; Aoudaghost, capital of these Berbers, located probably in the southwest and not far from Tichit, was a vassal of the black king of Ghâna and paid him tribute; an attempt at independence on the part of the chief of the Lemtouna motivated, around 990, an expedition by the king of Ghâna, who seized Aoudaghost and strengthened his authority over the sedentary Berbers and the "veiled Zenaga" of the desert, as well as expressed by several Arab authors2”

Arguing that the Moors could not have kept the form Zenaga to designate the Berbers living next to them and adopted another form, Assouanik, to designate the Soninké; he made a clear difference phonetically between the two names. Namely that, particularly with regard to the first vowel, which has always been written "a" and pronounced "a" or "é" by the Arabs in the name of Zenaga (Sanhadja, Sanaga, Zenaga), while it is clearly "o" or "ou" in Soninké.

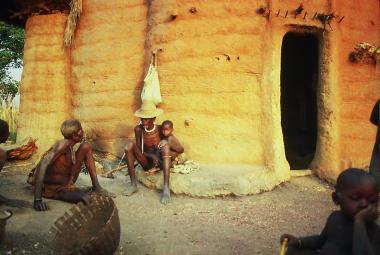

Even in his time, and despite Islamization, Maurice Delafosse found that the peoples of Black Africa had not experienced profound changes in their habits and customs, with their paganism and their use of charms, which reminded many respects of the peoples of ancient times: "The civilization of the Blacks itself does not appear to have undergone, as a whole, very profound modifications for thousands of years. At least there still exist today many Negro tribes whose material development seems to have remained at the same stage as it was in the time of the Pharaohs and whose clothes, weapons and tools are exactly identical to the clothes, to the weapons and tools carried by the Negroes depicted in the paintings and bas-reliefs of ancient Egypt.

The relationship of the Soninké - not necessarily biological but above all socio-ethnic - to the Sao can be made by various sources or cross-information as is possible with any other people in Black Africa. In this regard, there are the names – which could not be more important – apart from the rituals which are also, among other things, elements of identification which are rarely misleading. Some historians associate these fundamental characters with others more with regard to the Soninke, in this case their Islamic erudition or the fact of often occupying the functions of Imam, their propensity to travel far for commercial or religious reasons again. However, these three elements are not decisive in linking them to their distant Sao ancestors who were fiercely attached to their traditional deities and their traditions.

It is known that when a group emigrates, it often carries with it a portion of the land of origin. He sometimes also gives the place where he settles the name of the agglomeration from which he comes; a place of worship or an altar can also bear this name. A surname or toponym is therefore sometimes indicative of the origin of the occupants.

Wéréwéré Suleymane Konaté did not want to convert to Islamism when Soundiata came to power. The latter had sent him to Senegal to buy horses. After his return, he left the Mandé with his family, his possessions, his altars and his "secrets", gundo or gyindo. He led the exodus, and his descendants settled in the Bandiagara cliffs. Gyindo is the ancient Malinké term for “secret, mystery, secret knowledge”; however, this is the motto that all Dogon still wear today. »

It will be necessary to re-examine or reinterpret certain information or sources that we already had about the Soninké and other peoples and whose meaning or translation had been sacrificed for the benefit of their new uses or functions. In this case, the question must be asked whether the divinatory figures called Saw or Sao from the rock shelters of Koulouba really mean "rapid reading" or this term simply designates what they are used for without a direct link with the meaning of Saw or Sao. Namely read quickly through the sixteen painted geomantic figures (Eight geniuses and eight people) the future or to guess the secret messages of the deities or the Ancestors. Moreover, why the first of the sixteen codes of the divinatory art is baptized Sao.

From the offering called Sarakabaga by the mediator between men and God to the acceptance of the offering by God called Sarakaminèbaga, there is a whole world to know. Can only enter if one is initiated. And it is this decryption that is most lacking for Africans to regain knowledge of their past history. Islam and Christianity having, in the meantime, passed through this, the gap has widened further. To the point that there are no longer many people to know and explain the ancient traditions and their origins.

Even altered, names are rarely wrong in Black Africa when it comes to finding the distant origin of a person. If the Sokhona, Cissé, Touré, Diané, Khouma, Sakho lineages, among the Soninké, consider themselves as the distant and ancient lineages attached to the person of the Dinga or Dhinga Ancestor, there are some that are easier to attach to the recent migrations. This is the case of the Kamara, Kamissoko, Doumbia (or Sissoko), Bagayogo (or Sinayogo) and Danyogo to name only those who are specific to the Kagoro lineage of the former Empire of Ghana. “Because of their political role, these families were integrated and appear in the list of the 34 “families” of the Mandé, this list, which we published in 1955 (Dieterlen 1955:41 and 1959), grouping relatives and allies of the Keita, was established at the time of the founding of the empire of Sundiata. Representatives of each of them attend the seven-year ceremonies of the reconstruction of the sanctuary, during which their name and their origin are mentioned.

The motto of the five Blaw families is blaw mãsa so loolu "the five houses of the blaw chiefs". Each of them is still responsible for one or more particular cults whose origin is prior to the occupation of the Mandé and which were therefore imported from Ghana, for example:

- kɔnɔ in Krina for the Kamissoko,

- bɛmba in Dankassa for the Kamara,

- sɔda in Niengéma for the Kamara and in Karatabougou for the Doumbia,

- kuranle in Balandougou for the Sinayogo.

This last cult, that of the anvil, prerogative of the Sinayogo also called Togora, has a particular value, because it is linked to a sacred territory, that of Dakadyalan, birthplace and capital of Soundiata (Cissé and Kamissoko 1973-I: 79 and 1973-II: 112)5”.

The Kangaba through the Sanctuary of Kangaba or Kaba, even without knowing it, continued to convey a culture and a lexicon specific to the ancient liturgy of the Nile Valley. Like the Kama bolon, these two Kangaba terms of Kaba are in no way of recent use. We must go further and look for the reasons why the Kama bolon or Kamabulon (Roof of the sacred hut) is renewed every seven (07) years.

“Several contributions have been written on the famous septennial ceremonies of the Kamabolon in Kangaba, a village located ninety-five kilometers south of Bamako (Mali) and, probably, an ancient capital of the Mali Empire. The reports of G. Dieterlen (1955, 1959), followed by the publications of C. Meillassoux (1968) and G. Dieterlen (1968), have become classics in Mandinka studies. These two authors admitted the impossibility of recording the words recited in the Kamabolon shrine. These words are considered everywhere as the greatest secrets of the Manden, kept by the famous Diabaté family of Kéla, griots-clients of the former kings of Kangaba, the owners of the sanctuary6. »

Oral traditions indicate that the birth of the Empire of Mali is consecutive to the escape of Dankaran Toumani Konaté. Elder and half-brother of Diata Konaté who will later be known as Soundiata Keita or Soundjata Keita, Dankaran Toumani Konaté or Dankaran Touman Konaté was King of Manden. A usurper according to tradition since their sovereign father Naré Maghann Konaté had intended the throne after his death for Diata Konaté. It was before the eldest seized it once he breathed his last breath of the sovereign of the Mandingos. But during his reign, the latter was attacked by Soumaoro Kanté of the Sosso Kingdom. The usurper simply flees to save his head by abandoning his throne and his subjects. And it is there that the Mandinkas call on the heir designated during the lifetime of their father who had moved away from his half-brother to live in exile in Mema where he was now a great and formidable hunter. Soundjata Keita's army of hunters, further rallied by Fakoli Doumbia, Soumaoro Kanté's own nephew from whom he had stolen his wife, was strengthened. The coalition of these two forces made it possible to defeat Soumaoro Kanté during the battles of Kirina and Narena, who in turn fled to take refuge in the mountains of Koulikoro. This allows Soundjata Keita to become the new Mansa, and subsequently to build the unity of the Empire of Mali, by subdividing it into provinces at the head of which was a branch of the different clans of the coalition, namely the Keita, the Konaté, the Camara and the Condé. The royal name Keita that Soundjata Keita then took would thus derive from this resumption of the throne which was due to him in inheritance, in the sense that Kien would mean "Inheritance" and Ta to mean "To take", which would have given Kienta, in other words " Take your inheritance” and by progressive alteration Keïta. But this could be just one interpretation among many. Because Kien or Kienta or Keita have been intimately linked since the highest antiquity in ancient Nubia and designate one and the same thing: the

Sacred or the King-Priest. In any case, it is to Soundjata Keita that we owe the gathering of the allies at Kaaba which gave birth to the Charter of Manden or Charter of Kourakan Fouga and which remains the most significant intangible heritage of this singular Mandinka epic.

The Charter of Manden or Charter of Mandé or Charter of Kouroukan Fouga, proclaimed in 1222 in what was the Empire of Mali under the reign of Emperor Soundiata Keita (1190-1255), was proclaimed in the plain of this region of Kangaba. Today UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage, it is considered by many to be the first Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The Kamara or Camara are considered the oldest lineages made up essentially of hunters who left Oualata in Ouagadou or Wagadou due to drought to go and found Manden or Mandé. By becoming an autonomous people, these old lineages of Power of the former Empire of Ghana will give birth to new other peoples, either by divergence like the Bambara or the Dioula, or by interbreeding with the Fulani like the Khassonké. The research of G. Dieterlen in Mali constitutes a precious mine of information on this subject. They have the image of those of Léo Frobenius on the Wasangari or Ouasangari in the old Borgou (Benin-Nigeria) about the Kissira Migration. But it is still necessary to know or be able to decipher all this information which says a lot that it does not appear there for the layman. The study of the cosmogony, ancient names, rituals, agricultural practices of the Soninke and their descendants allow those who master the secrets of the traditions and ancient languages specific to these peoples to be able to establish links without great difficulty real or possible with other peoples in Black Africa.

By Marcus Boni Teiga

Marcus Boni Teiga is a journalist and writer, specialist in ancient Nubia and author in particular of THE SAO OF LAKE CHAD An ancient and mysterious civilization in the center of Black Africa, Editions Complicités, Paris, 2023

1 C. Cheikh, Aperçus sur la situation socio-linguistique en Mauritanie, © Institut de recherches et d’études sur les mondes arabes et musulmans, 1979 : https://books.openedition.org/iremam/1235?lang=fr

2 Maurice Delafosse (Ancien gouverneur des colonies, Professeur à l’école coloniale et à l’école des langues orientales), Les Noirs de l’Afrique, Payot & Cie, Paris, 1922 Édition réalisée pour herodote.net, https://www.herodote.net/Textes/delafosse_noirs_afrique.pdf 56

3 Ibid.

4 Référence papier Germaine Dieterlen, Premier aperçu sur les cultes des Soninké émigrés au Mande, Systèmes de pensée en Afrique noire, 1 | 1975, 5-18. Référence électronique Germaine Dieterlen, Premier aperçu sur les cultes des Soninké émigrés au Mande, Systèmes de pensée en Afrique noire [En ligne], 1 | 1975, mis en ligne le 2 juillet 2013, consulté le 20 août 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/span/93 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/span.93 57

5 Référence papier Germaine Dieterlen, Premier aperçu sur les cultes des Soninké émigrés au Mande, Systèmes de pensée en Afrique noire, 1 | 1975, 5-18. Référence électronique Germaine Dieterlen, Premier aperçu sur les cultes des Soninké émigrés au Mande, Systèmes de pensée en Afrique noire [En ligne], 1 | 1975, mis en ligne le 2 juillet 2013, consulté le 20 août 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/span/93 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/span.93

6 Référence papier Walter E. A. van Beek et Jan Jansen, La mission Griaule à Kangaba (Mali), Cahiers d’études africaines, 158 | 2000, 363-376. Référence électronique

Walter E. A. van Beek et Jan Jansen, La mission Griaule à Kangaba (Mali), Cahiers d’études africaines [En ligne], 158 | 2000, mis en ligne le 12 juin 2004, consulté le 20 août 2021 : URL : http://journals.openedition.org/etudesafricaines/177 ;

DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesafricaines.177 60